Please click on the map,

the region you want to visit |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Folklore Museum in Stemnitsa |

|

A few words about Museum's Foundation

Stemnitsa, known from its history, day by day began to change in a deserted city rather than rewarded for its contribution in the struggle. Reasons, such as the mountainous terrain and the conditions of access to major centers, resulted in stagnation and in a high current expatriation. This created the need for the revitalization of the site, which led to the founding of the Folklore Museum of Stemnitsa.

The Folk Museum of Stemnitsa opened on September 1, 1985. The work on the organization began two years earlier with the aim of highlighting the society of Stemnitsa and the arts, and of familiarizing Stemnitsa's people with the modern works of craftsmanship.

Having this in mind three themes were formed:

- The rich, numerically and qualitative, collection of the founders, which includes items from many places of our country.

- The rich history of growth and development of arts.

- The internal architectural layout and decoration of houses.

|

|

|

Visits Visits |

From 1/10 - 30/6

Daily 10 am - 1 pm

Weekend 10 am - 2 pm

Every Tuesday closed

From 1/7 - 30/9

Monday and Sunday 10 am - 1 pm

Wednesday - Thursday - Saturday

10 am - 1 pm and 6 pm - 8 pm

Friday, 5 PM - 8 PM

Every Tuesday closed

Contact:

Mrs. Victoria Frentzou

Tel: 27950.81.252 |

|

|

| On the ground floor, a representation of the workshops of artisans is presented. At the mezzanine and at the staircase leading to it, the traditional architecture and the equipment of Stemnitsa's house are exhibited. At the single first floor, the diverse original collection of Savopoulos is exposed in showcases, which is composed of Byzantine icons, weapons, pottery, metalwork, woodwork, needlework, textiles and accessories from traditional costumes.

The building

The Folklore Museum of Stemnitsa is housed in a three -floored building of the 18th century, which was built, according to tradition, to serve the needs of a large family. The tradition attaches to it a historical significance because there the chieftains meetings took place in 1821and also the convening of the First Peloponnesian Senate on May 29, 1821.

This building has rectangle ground plan and is three-floored.

The ground floor or basement served as a stable and there the wood and the wine in a huge "cask" were stored.

On the mezzanine or Messiano, there were "Yukos" and the food.

Finally, the top floor or upper floor was the principal area of the residence.

The house originally belonged to the Tsepre family. Then, came to the Alexandropoulos family and lastly to George Hatzis, whose six sons donated it to Trikolones association, which, in its turn, donated the house with full ownership and possession for the purpose of establishing the Folklore Museum of Stemnitsa.

The house, with the passage of time was collapsing, but thanks to the willing assistance of donors, Hatzi's brothers, the assistance of Evangelos Kallaniotis and the noble patriot Athanasios John Martinos, became the renovation of the building by the architect Mrs. Sula Moutsopoulou.

On the same time done the formation of the outer part, while the interior design was done by architect Mrs Eleni Economides.

|

Stemnitsa

Stemnitsa, a beautiful town of Arcadia, is built on the slopes of Mainalo Mountain. The first post-Byzantine period of Stemnitsa is lost, and only in 16th century we find the first written references to it. From the 18th century, with the population growth, Stemnitsa developed into an important village, into a Chora as it was called, while presented intellectual, artistic and economic development.

During the struggle, Stemnitsa offered much, along with its neighboring cities of Gortynia. Typical is the address that the Prime Minister Th. Deligianis gave to the residents of Stemnitsa: "The residents of Peloponnese are the smartest among Greeks. Arcadians are the smartest in Pelloponnesse, smarter than Arcadians are Gortynians and smarter than Gortynians are Stemnitsa's residents".

Stemnitsa's prosperity continued throughout the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, when the emigration to foreign countries and also to Greek urban centers was generalized, and then began the wilting of Stemnitsa. The old Chora Stemnitsa with 3,000 residents is today a village with a small population, which, however, keeps alive its rich history. |

|

|

The Arts

Stemnitsa's residents, famous artists, especially from the 17th century to the early 2nd century, were distinguished especially in the processing of metals, from which every kind was used, from the simplest to the most valuable.

The result was Stemnitsa to experience a great glory, thanks to coppersmiths, the bronze-smiths and especially the goldsmiths.

Coppersmiths, Kalantzides or Kazantzides are the artisans of copper. They were making whirring constructions, collages with rivet or links, having as basic tools the hammer and the anvil.

Bronze-smiths are the craftsmen who were working with bronze, the brass. The bronze objects (such as bells, the candelabra, the weights and a group of exquisite in tone bells) were manufactured with the cast technique.

From these items of construction and from their specialization in each one, the bronze-smiths are known also as bell-smiths.

"Goldsmiths" were called the craftsmen who made the most small and precious objects of silver and gold. The quantity of goldsmiths of Stemnitsa was numerous, and their fame was spread throughout the Balkans.

Apart from the artisans of metals, in Stemnitsa flourished also and other traditional craftsmen. These artisans were mainly concerned with the manufacture of clothing accessories such as pasades for the thick woolen clothes, the tailors who sewed and embroidered costumes, and even the cobblers, or others that made these necessary items for the various occupations of the residents, as the saddle makers or Samartzides, the farriers, and the coopers.

Many craftsmen from Stemnitsa were practicing their art in permanent workshops, but they were also itinerant workers. They traveled the longest time and they reached far beyond the boundaries of Arcadia and Peloponnese. They even arrived in the Ionian Islands and to the famous Istanbul and from Egypt and Cyprus to Danube.

These trips were being made by organized groups of artisans, the Kompanies or Bouloukia as they were called. Those travels were divided into two kinds, the long trips of many months and the trips lasting a few months. But there were also the artisans who made very close and short trips, just to meet temporary needs. |

The Goldsmith

The art of goldsmithing required an innate talent, great skill, sensitivity and physical stamina. Depending on the social, economic and seasonal conditions, the goldsmith pursued his art either by touring or in Stemnitsa, in his permanent workshop.

The material mainly used was the silver and rarer the gold. Often they made gilded objects that were made of metal impurities.

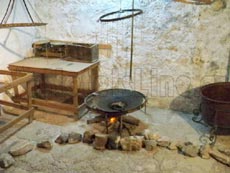

He put his tools on a special bench (at the workshop) or on a small chest (on tours). The metal was melted in a special furnace with the help of bellows and the most valuable metals into special small clay cones.

Items manufactured by goldsmiths are distinguished, according to their purpose and their use, into secular (jewelry for traditional women costumes, accessories for men's weapons and household utensils), religious (crosses, chalices, candles, censers, covers for icons, Gospels) and others.

The main techniques with which Goldsmith was processing silver and gold are the cast, the forged or the inflatable and the wire, while the decoration is completed with the engraving or carving. The creations of goldsmith are adorned by precious or ordinary stones, with enamel or niello. |

|

|

The Tinker

The tinker's or Kalatzis art was been practiced by coppersmiths, the craftsmen who made any kind of bronze objects such as utensils for the daily needs of a home or simple sacred vessels.

The bronze objects, especially those used for the needs of the house, often must be coppered to protect the surface from oxidation.

The tinker's tools are the tweezers, with which holds the bronze over the fire, and the copper pan, a large tin, in which puts the flakes of surplus in order to use them again.

Materials used are: the match (hydrochloric acid), the lisiantiri (ammonium chlorides), sand or kourasani (grated tile) and, of course, the solder.

The tinker has the following schedule: first he cleans the pan and coats the inner surface with match and then rubs it with sand or kourasani. Then, he heats the pan and coats it inside with lisiantiri. After that, he throws the solder to melt and after that, he spreads it with a cloth or cotton. The nuggets of surplus from solder are gathering in davas. Finally, he polishes the bronze with a cloth. |

The chandler

The chandler can bring his art to a simple place, preferably on the ground or the lower floor of the house, which has a fireplace with a low chimney.

To make the candles and the torches, he uses string and wax. His tools are the cauldron, the cap, the rim or frame for the melted wax, the spinning wheel and the frame for the wicks. Necessary also are a bucket and the pot, a spoon and pieces of burlap or other thick cloth to filtrate the melted wax. Finally, he needs a bench to put the ready candles and scales for the weighing of candles he sells. |

|

|

The cobbler

He is the person whose job is to mend all kinds of shoes. The art of the cobbler, or rather the profession, usually was practiced by some of the farmers. A humble profession without creation claims, but still useful.

It is a relatively easy art, because a fully equipped laboratory wasn't necessary, only a few awls (stabbing, scissors, and pliers) and a small bench. |

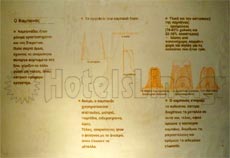

The Bell-maker

"The art of bell will be there as long our religion will", said an old bell-maker. The bell-makers had their permanent workshop in Stemnitsa, where they made small structures that were easily transported, but mostly they were travelers. Having the necessary tools loaded on animals, they were travelling to the villages and cities, where they set up a simple or a relatively permanent workshop, especially when the orders for new construction were numerous.

The basic element that the bell-maker needs is bronze, brass. The bronze - which is a mixture of copper and tin - is used for the construction of the bell in the ratio of 78-82% for copper, of 22-18% for tin. The additional materials needed to make the molds for the bells are bricks, the mud from a special soil, red soil or Aspropoulia.

Tools of the bell-maker are the wreath, which is the horizontal base of the structure, the frame or pantefti, the outer iron mold in shape of a cone and treso or modelo or wheel, a type of diabetes that is adjusted to form the interior and the external mold of the bell. Furthermore, he is using trowels, trowel, pliers, and iron-saws and arnaria (rasps). Finally, the oven is necessary with the blower, in which the metals are melted. |

|

|

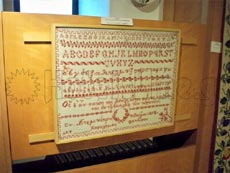

The trousseau

The marriage contracts give us the opportunity to briefly mention the institution of trousseau. It is embroidered and woven fabrics of clothing and of home that the newlywed woman was bringing when she got married with her and belonged exclusively to her. In case of death, and if she was childless, the clothes were going back to her family house. The trousseau was her movable property, which, typically, was prepared by herself with the help of her mother.

The institution of trousseau is distinguished by the one is given as dowry before the marriage. The dowry in the form of money or property was not always an obligation of parents to their daughter while the trousseau, even a small one, was not missing from any girl at the time of her marriage. Sometimes the dowry can not be distinguished from trousseau because with this format, particularly in rural communities, the girl took her dowry as compensation for her work in fields and her participation in production.

The dowry was a concern for all the family but the trousseau was the mother's duty. Even today the mother is largely responsible for persuading and encouraging her daughter to the idea of marriage and of trousseau.

A rich symbolism is hidden in this story of the trousseau. The girl with the trousseau was showing to her new family, her good relations and ties with her family, who ensured to equip her with the necessary household.

The significance of the trousseau firstly highlighted by the fact that the trousseau was and still is a major transaction of marriage and secondly, with their exhibition, a social competition is manifested.

The woman in traditional Greece was taking her new position from the trousseau and all the symbolism behind it. The marriage in conjunction with it, gave to woman a recognized place in society.

With the exhibition of trousseau, the woman was showing her abilities and also the financial standing of her family. Also, in times when the single women were not going either in the village or other public places (only in the Church), this exhibition of the trousseau was combined with the first social appearance - "exhibit" - of the daughter through her handmade works. Thus, this custom was, until recently, the intersection of two spheres: of public and private life. It was the creation, for the first time, of a social transaction between the woman and society.

Over the years, the form of trousseau has changed, since the items are not longer handmade but industry items. The whole mental and organic energy that was given on their construction goes now on their buying and is a financial investment.

The interesting fact is that the whole equipment, even the new house, are decorated with industry items that have embroidery and lace that are manufactured in imitation of handmade, which proves that the tradition continues unconsciously, subservient to modern methods and needs. |

Ceramics

The Savvopoulos's collection includes important works of Minas Avramidis and N. Theodorou, two of the most important famous Greek folk ceramists.

The collection consists mainly of dishes, the surface of which is privileged to "accommodate" the complex subjects of Minas Avramidis.

The subject matter and the style of Minas Avramidis have certainly taken elements from both the Byzantine and the Eastern angiography.

But his works are unique and completely his own.

The objects in the collection are divided into the following topics:

1. Old Testament and Orthodox Iconography

2. Byzantine and Eastern Tradition

3. Ancient Greek History and Mythology

|

|

|

Embroidery

Cretan Embroidery

The Cretan embroidery that is exhibited in the museum (dimensions 1.67 x 0.4 m) is a part of women's aprons that was worn in the middle of last century. Rarely the shirts are intact, which are generally wide down and narrow on chest.

These aprons have one fixed type of repeated motifs. The tailor seems to respect the tradition as he is not strayed away from the design, color and stitch. Mermaids, birds and carnations are the dominant motifs. They are divided into monochrome (blue thread) or colored aprons (combination of orange, green, blue and yellow thread). The main stitches are the Cretan wheel or chain, the herringbone, the satin and the French knots.

With these embroideries, that have survived in part, Greek and foreign scholars have dealt, because they are truly masterpieces made by Cretan women. The elements, which represent the importance of this embroidery, is the rich decoration, the subjects of which are clearly showing influences from Byzantium (double-headed eagle), East (flowers into the vase) and West, from the eve of the Venetians on the island until the 17th century.

There are aprons that are dated from the 18th century, mainly pieces that are (in stores and exhibitions) in English Museums (Victoria & Albert Museum in London) and in American Museums (Textile Museum in Washington DC). In Athens, there are similar embroidery on the collections of the Greek Folk Art Museum and of Benaki Museum. |

Costumes

For the exhibition on the second floor of the Museum have been selected the most representative items and the entire costumes from the mainland and the islands of Greece.

Thus, the subjects - shelves have been divided in:

- costumes and accessories of Karagounides and Sarakatsan,

- costume of the bride from Salamis

- shirts, segouni and shoes from different regions of Greece.

|

Costume of Karagounides and Sarakatsans

The Karagounides and Sarakatsans are two groups with unique art that is evident in their costumes. The male and female costume of each group is distinguished by different colors, patterns and they are woven and embroidered in different parts. All these differences are due to a typical and social-economic conditions, customs and traditions.

The Karagounides farmers, residents of the plain of Thessaly, were always a permanent population because of the nature of the economy as opposed to Sarakatsani who were breeders, so they were forced to move constantly to ensure food for their herds. |

|

|

Icons

The collection of icons of John and Irene Savopoulos, fruit of their love for Greek things, come from the seller of antique, Giorvasi Tozakoglou, who had an antique shop in Istanbul until 1938. Then, he transferred it initially to Thessaloniki and later to Athens.

The icons of Stemnitsa Museum are placed chronologically, except from one of the late 17th to 18th century, but most belong to the 19th century.

That includes a range of artistic creativity over the two hundred years coming mainly from the laboratories in Northern Greece, a place where painting flourished in the 18th and 19th century.

It is important that the eighteen icons of the collection are dated with an inscription, some bearing the names of their donators and eight of them the signature of their painters.

Also, in four cases, there are family's remembrances on the back of the icon, such as birth dates. This makes the collection more interesting from an archaeological point of view, because it provides to the investigation, a safe comparative material for dating and assessment of the rich production of icons of the later years of Ottoman rule.

In addition, the historical information provided to us by these few signs, help us to outline the social history of that era.

Unfortunately, the study of art of these years is still in its infancy and mainly whatever concerns to the popular expression of the religious paintings, a fact that forces us to use approximately dates and identification of workshops.

|

Information - Texts: Folklore Museum in Stemnitsa

Photographs: Myrto Adamantiadis |

|

|